Until now it has been assumed that less activity from the Sun equates to less warming of the Earth.

But the new research, which focuses on a three-year snapshot of time between 2004 and 2007, suggests the opposite may be true.

As solar activity waned at the end of one of the Sun's 11-year cycles, the new data show the amount of energy reaching the Earth at visible wavelengths rose rather than fell.

Scientists believe it may also be possible that during the next up-turn of the cycle, when sun activity increases, there might be a cooling effect at the Earth's surface.

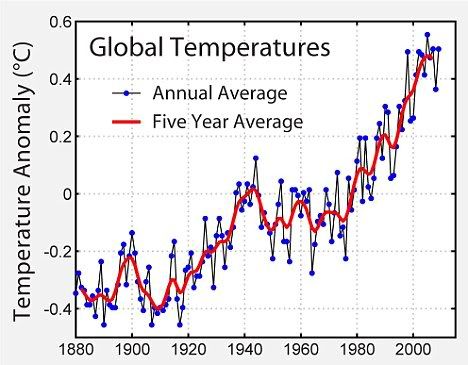

A further twist arises from the fact that over the past century, overall solar activity has been increasing.

If the new findings apply to long as well as short time periods, this could translate into a small degree of cooling rather than the slight warming effect shown in existing climate models. It would effectively turn received wisdom on its head.

Sceptics are likely to say the results further undermine the reliability of climate change science, especially with regard to solar effects.

Professor Joanna Haigh, from Imperial College London, who led the study, said: 'These results are challenging what we thought we knew about the Sun's effect on our climate.

However, they only show us a snapshot of the Sun's activity and its behaviour over the three years of our study could be an anomaly.

'We cannot jump to any conclusions based on what we have found during this comparatively short period and we need to carry out further studies to explore the sun's activity and the patterns that we have uncovered on longer timescales.

'However, if further studies find the same pattern over a longer period of time, this could suggest that we may have overestimated the sun's role in warming the planet, rather than underestimating it.'

Speaking at a news briefing in London, she denied that it would fuel scepticism about climate change research.

'I think it doesn't give comfort to the climate sceptics at all,' she said.

'It may suggest that we don't know that much about the Sun. It casts no aspersions at all upon the climate models.'

The research, published in the journal Nature, is based on data from a satellite called SORCE (Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment) that has been measuring the Sun's energy output at X-ray, ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared wavelengths.

Prof Haigh's team found that, above an altitude of 28 miles, concentrations of ozone in the atmosphere increased as total solar output decreased.

The ozone rise accompanied a steep fall in levels of ultraviolet radiation.

Closer to the ground, an increase in visible radiation caused heating of the lower atmosphere.

'At face value, the data seem incredibly important,' Michael Lockwood, a space physicist at the University of Reading, told Nature.com.

'If solar activity is out of phase with solar radiative forcing, it could change our understanding of how processes in the troposphere and stratosphere act to modulate Earth's climate.'

'The findings could prove very significant when it comes to understanding, and quantifying, natural climate fluctuations,' he added.

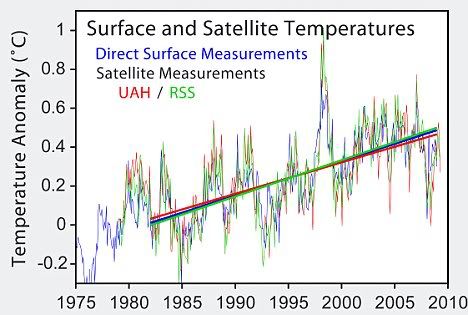

'But no matter how you look at it, the Sun's influence on current climate change is at best a small natural add-on to man-made greenhouse warming.'

'All the evidence is that the vast majority of warming is anthropogenic. It might be that the solar part isn't quite working the way we thought it would, but it is certainly not a seismic rupture of the science.'